1974

November 14, 20171976

November 14, 2017At the start of the year Boetti took part in the group exhibition “24 ore su 24 ore” at the Galleria l’Attico run by Fabio Sargentini, exhibiting fifty drawings of Bombe ordigni origami e altro traced on extra strong paper, Estate 70 (the roll 20 meters long which he made in 1970) and some photographic enlargements of jokes about contemporary art clipped from newspapers and collected under the title of Riso (“Laughter”).

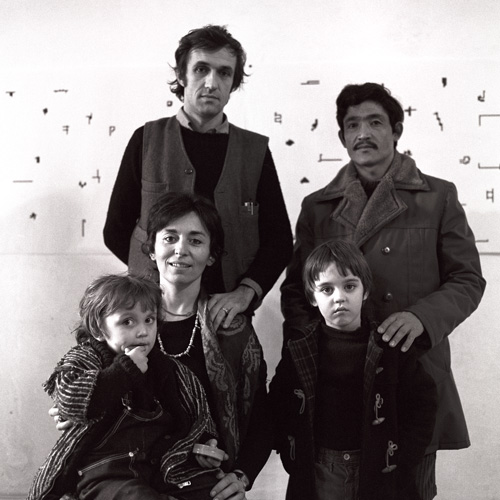

Alighiero Boetti with Annemarie Boetti, Agata, Matteo and Salman Ali, photo by Giorgio Colombo

In January and February he spent a whole month in New York with his wife, children and Salman Ali preparing his exhibition at the John Weber Gallery. They stayed in a loft at 10 Bleecker Street in the Tribeca district. He made friends with LeWitt, Weiner, Kossuth and Bochner. This was his second solo exhibition at the gallery. It opened on 8 February, with two large works on squared paper, Storia naturale della moltiplicazione and Trentuno per trentuno più trentanove. The exhibition was accompanied by an offprint of Tommaso Trini’s 1972 text, “Come non deragliare parlando di Alighiero Boetti.” Trini himself reviewed the exhibition in the June number of Data. The only American review, by Susan Heinemann in Artforum, was very critical.

Weber also organized a seminar for the artist at the Art School of the University of Hartford, where AB did some performances, including Due modi diversi di fare due cose diverse and Raddoppiare dimezzando. Attempts to persuade New York University Press to publish the Libro dei Fiumi in an English version proved fruitless.

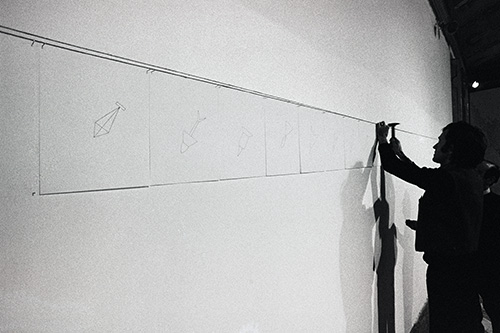

Alighiero Boetti prepares the 42 bombs, photo by Giorgio Colombo

On returning to Italy, Annemarie Sauzeau reflected on the experience of three years of America (the Galleria Weber, MoMA, universities and publishers) and wrote to their faithful friend John Weber: “Our conclusion after New York, for example after reading the reviews of exhibitions, is that Alighiero’s work and he himself are not understood in America. You are an exception because you have understood him, and that’s wonderful. I say this without indignation, it’s all for the best and things will change. I’m only referring to the current situation…”.

In May, Boetti had a solo exhibition at the Galleria Pasquale Trisorio in Naples: “boetti 1966.” It presented works from the Arte Povera period: Scala, Sedia, Mancorrente metri, PING PONG, Zig Zag, Mimetico, panels with words: CLINO, stiff upper lip and the triptych on cardboard 01.130 verde vagone, 1133 rosso adrianopoli, 2233 bleu positano.

In Munich, the Area Gallery presented a small solo show, “Zwei,” dealing exclusively with the theme of the double. The catalog was edited by Bruno Corà. The exhibition was repeated in November in the Florence venue, with the addition of a reading from the Koran, his favorite objet trouvé. He had bought a number of copies in Kabul to give as presents (at times with his name engraved in them). In June a solo exhibition at the Galleria Sperone in Rome again presented Storia naturale della molteplicazione.

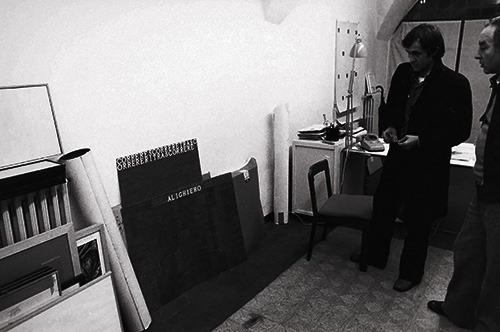

Alighiero Boetti at the Banco / Massimo Minini Gallery, 1975, photo by Ken Damy

In the summer Boetti traveled widely in Sudan and Ethiopia, sending back his postal works, which included Codice, Eritrea libera. He reached Harrar, as a tribute to Rimbaud in Abyssinia. Three years later he recalled:

“Rimbaud arrived in Africa by ship. That certainly was an adventure. In 1975, when I was in Ethiopia, a boy asked me in English if wanted to see Rimbaud’s house. I asked who he was. ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘a person who gave French lessons.’ I realize the imagination now offers nothing like that ship that carried people towards new horizons.”

In October at the 13th São Paulo Bienal in Brazil, he was represented by Storia naturale della moltiplicazione. It was chosen by the commissioner for the Italian participation, Bruno Mantura.

In September he intensified the reordering, begun in ’73 with Rinaldo Rossi, of the profusion of his drawings, photographs, performances and ideas, to complete the portfolio Insicuro noncurante. It was presented on 23 October at the Saman Gallery in Genoa. A drawing made up of dashes and crosses on squared paper, originally titled I pini non crescono in un giorno, underwent further development. In the folder Insicuro noncurante it was inserted with the outline doubled and given the new title Verificando il dunque e il poi se ne andò piano piano verso il canto di una pineta (a quotation from Metastasio). In 1979, transferred to fabric embroidered in white on white, the drawing became L’albero delle ore. Boetti explained the triangular form of the composition in these words:

“The bell tower of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere sounds the hours and quarter hours with two different notes. So at every quarter hour you hear at the very least one stroke (at 1 o’clock) up to a maximum of fifteen (at 12:15). This progression, transcribed into two signs like two notes, forms a double triangle, of day and night.”

This year there appeared three small drawings: Gradine, a human outline slumped across some steps, Giogare and San Patrick, which were subsequently integrated into two large drawings on light paper, both titled Collo rotto braccia lunghe (1976).

“I did that work thinking about someone who was able to turn his neck 360 degrees—a broken neck obviously—and then I thought about the blind person interviewed by Diderot on the problem of blindness. Diderot was obsessed by this problem, he’d done a whole book about the blind. He interviewed them, asked them what a mirror was and so on. He asked one if would like to see the moon and he replied no, but he’d like to touch it, to have hands so long he could touch it…, the desire to touch from afar…”.

The Boetti completed Classifying, the thousand longest rivers in the world. While continuing their search for a publisher, AB prepared to transfer the list to fabric with a view to having one or more tapestries embroidered in Kabul with the title I mille fiumi più lunghi del mondo. In preparation, he designed three small test pieces and had them made up over the same years. They showed the names and lengths of the rivers written in “pixels,” which would be embroidered in three color variants. In the two large definitive versions, begun in ’76, the entire list of rivers unfolds in horizontal lines about five meters long, arranged in descending order (from the longest, the Nile-Kagera, down to the thousandth, the Agusan).

Alighiero Boetti with some of his works on deposit at the Galleria Banco / Massimo Mini, Brescia, photo by Ken Damy

Through Francesco Clemente, AB met Giovan Battista Salerno, a young art critic with whom he formed a strong and enduring intellectual affinity. Between his other friendships that with Mario Schifano, whom he had met in his early years in Rome, was strengthened. Of their relationship, Salerno observes: “I believe that Alighiero respected a certain eclectic freedom in Schifano, the fact that he went in for cycling and Polaroid photos! Eclectic, not amateurishly but as an encyclopedic way of drawing on practically everything, from movies to parties or bicycle design. I think it brought them close together.”