1991

November 14, 20171993

November 14, 2017In February 1992 Boetti’s third child, Giordano, was born.

AB with Giordano, 1992, courtesy Caterina Raganelli Boetti

On 11 February, a solo exhibition opened at the Galerie Franck + Schulte in Berlin. It presented sixteen items divided between works on paper, in ballpoint and embroideries. The Mappe exhibited, dating from ’78, bore the words “in Kabul chaos reigns” running around the border.

In speaking of that distant “chaos” whether preceding the Soviet invasion (’79) or the civil war in post-Soviet Afghanistan, AB expressed his disenchantment and his extraordinary farsightedness about Taliban fundamentalism in conversation with Nicolas Bourriad in Paris:

“The Afghans’ strength of resistance to our civilization has always amazed me. Nothing ever changes. All the same, I hope Massoud returns to power. His opponent Makhtiar wears a black turban, the turban of Khomeini… And we know far too well what he gradually built his power on, starting from ’72/73. The Shah imposed on the Iranians Westernization to the bitter end, to a ridiculous degree. I remember the whores in miniskirts in Tehran. Warhol did a portrait of Farah Diba… In Afghanistan something similar happened, but it didn’t last long. One of the king’s sons even opened a nightclub in the embassy district of Kabul, it was called ‘24 Hours.’ But it closed after four months. The problem is no one was capable of emerging as a moderate on either side.”

The ten large tapestries embroidered to designs by Boetti and Paladino returned from Peshawar. They were exhibited at various venues: Emilio Mazzoli’s gallery in Modena, the Italian Institute of Culture in Toronto, the International Center of Contemporary Art in Montreal and finally, between December and January ’95, at the FRAC in Lille. In the meantime, on 25 September, the Galerie Leccese-Spruth in Cologne presented the group of fifty-one tapestries with poems by Sufi Barang which had been exhibited at “Les Magiciens de la Terre” the previous year.

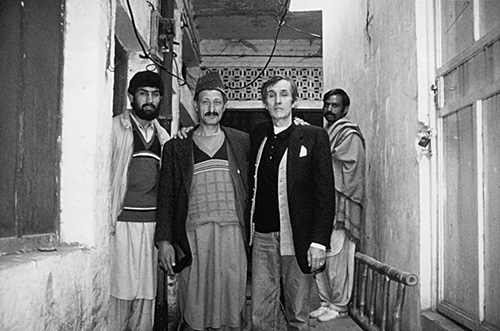

Boetti with Maestro Azam, 1992, courtesy Caterina Raganelli Boetti

On 28 September, the Kunstverein in Bonn inaugurated the important solo exhibition curated by Annelie Pohlen, which then moved to Münster and Lucerne. The title was taken from a text by Gustav Jung, Synchronicity as a Non-Causal Principle of Events.

It was chosen by AB both for its content, close to his favorite subject of “happy coincidences,” and because it lent itself to being inscribed (in German, consisting of forty-nine letters) in a magic square of 7 × 7. The subtitle was “Alighiero e Boetti 1965–1991.” The invitation to the exhibition also presented the quotation in German in gold on a red ground arranged in a square.

For the occasion, AB recreated Panettone (the original had been destroyed) and a second version of Io che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969.

The catalog was a very lively experiment: AB himself asked a group of critics to each write on one work. In addition to the curator‘s introductory text, there were therefore thirty-five essays specially written for the exhibition.

Among the innumerable group exhibitions, three held abroad were notable. Two were in France in June: “A visage ouvert” at the Fondation Cartier at Jouy en Josas and “La Collection Christian Stein, un regard sur l’art italien” at the Nouveau Musée of Villeurbanne. One was held in Osaka in October: “Arte Povera” at the Kodama Gallery.

For the exhibition at the Magasin in Grenoble, scheduled for late ’93, AB began work on fifty khilim rugs in collaboration with Adelina von Furstenberg, director of the art center. He designed them to the same rule as Alternando da 1 a 100 e viceversa. In September ’92, on the basis of grids supplied by the Studio Boetti, fifty cartoons were drawn by students at thirty art schools in France and some twenty friends or relations. Subsequently his assistants in Rome transferred these drawings to the definitive scale (200 × 200 cm) for twenty weavers in Pakistan, who began work on them in early ’93.

Of the fifty khilim, Salerno wrote: “A design that starts from Rome, goes to France and circulates in some thirty towns, returns to Rome, leaves for Peshawar in Pakistan and is finally concentrated in Grenoble, travels the same distance that divides Oslo from the Bering Strait in a straight line along the sixtieth parallel, meaning the whole of Asia.”

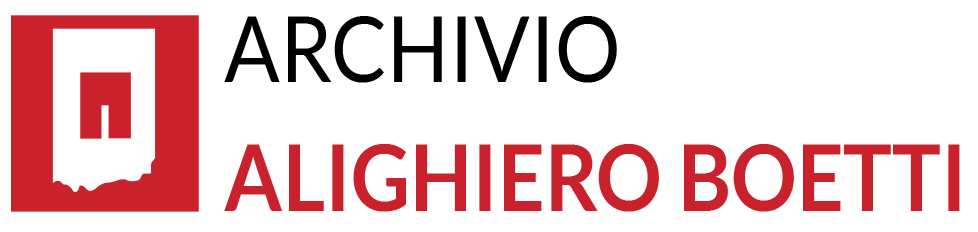

AB went to Peshawar to meet the master carpet weaver Azam. He also made a journey to that “region of the soul,” as Caterina, who accompanied him, recalls, amid the mountains whose Pakistani side he had never seen before. It was “the last destination visited, the region of Rakaposhi (7,788 meters) in the mountain system of Korakorum which, continuing the Himalayas westward, joins up with the chain of the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan.”

AB had himself photographed by Caterina in a pantheistic gesture, in which the opening of his arms accompanied the mountain slopes, while his head, in the middle of the picture, was aligned with a snowy peak.

In preparation for the exhibition, the Afghan embroiderers of Peshawar were entrusted with a hundred small multicolored squares titled De bouche à oreille, which became the title of the exhibition as a whole. In the third phase of the project, AB planned an immense Lavoro postale based on a numerical progression going from one envelope with a stamp up to 121 envelopes (11 × 11): in all 39,976 stamps. The envelopes contained drawings and all of the drawings were exhibited beside the envelopes. The whole constituted an immense “carnet de voyage,” made up of parcels that really had traveled across France for weeks, with the collaboration of the Ministère des Postes, and like the preparatory drawings for the khilim, had made more than one journey between France and Italy to converge in the end on Grenoble.